What Is Response Bias? | Definition & Examples

Response bias refers to several factors that can lead someone to respond falsely or inaccurately to a question. Self-report questions, such as those asked on surveys or in structured interviews, are particularly prone to this type of bias.

The applicant thinks that, since this is a customer service job, the company is probably looking for someone who enjoys meeting new people. Despite being an introvert at heart, the applicant answers “yes” in an attempt to increase their chances of being hired.

Because respondents are not actually answering the questions truthfully, response bias distorts study results, threatening the validity of your research. Response bias is a common type of research bias.

What is response bias?

Response bias is a general term describing situations where people do not answer questions truthfully for some reason.

This occurs because of the way we integrate and process multiple sources of information when we answer a question in an interview or similar setting. Respondents may answer inaccurately for a variety of reasons:

- Desire to conform to perceived social norms (social desirability bias)

- Desire to appear favorably to interviewer or other participants while being observed (Hawthorne effect)

- Desire to perform in line with the research objectives, perhaps due to having guessed the aims of the study through demand characteristics

- Desire to finish survey questions quickly, or lack of interest

In practice, this means that any aspect of a study can potentially cause a respondent to answer in a biased fashion.

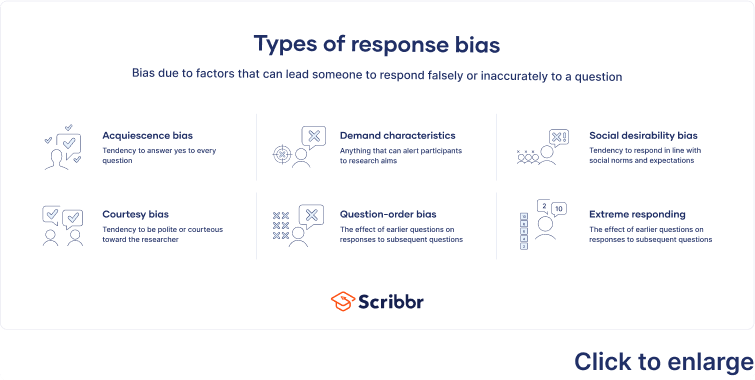

Different types of response bias

There are several types of response bias, categorized based on what causes the bias. Common types of response bias are:

- Acquiescence bias: Respondent tendency to answer “yes” to every question, regardless of what they really think. This often occurs with surveys that include only or mostly binary response options, like “Yes/No.”

- Demand characteristics: Anything that can alert research participants to the goals of the study. The title of the study, the tools and instruments used, or even the researchers’ interactions with the participants can all lead participants to alter their behavior based on what they think the research is about.

- Social desirability bias: Respondent tendency to distort responses in order to bring them more in line with social norms and expectations. For example, when asked about their drinking habits, respondents who drink on a daily basis may feel inclined to conceal this, fearing that they may be perceived negatively by others or by the researcher.

- Courtesy bias: Respondent tendency to be polite or courteous toward the researcher. It is common in qualitative research designs (e.g., face-to-face interviews). For example, when consumers are asked about their opinion on a product, some may downplay their frustration or lack of satisfaction for fear of being impolite.

- Question-order bias: Risk of questions that appear earlier in a survey or questionnaire affecting responses to subsequent questions. Earlier questions can serve to set context, influencing how respondents interpret the questions that follow. For example, asking respondents which basketball team is their favorite and then immediately following up with a question about which sport is their favorite is likely to result in more respondents indicating a preference for basketball.

- Extreme responding: Respondent tendency to choose only the highest or lowest response available, regardless of their actual opinion. For example, in a Likert scale survey with response options ranging from 1 to 5, there is a risk that a respondent will only choose the 1s or the 5s throughout the survey.

Response bias examples

In experimental designs, response bias can influence participant behavior due to demand characteristics. Here, the result or response that the researchers expect is accidentally suggested to participants.

Participants are randomly assigned to either a group told that menstrual cycle symptomatology is the focus of the study or a group to which no interest in menstrual cycle symptoms is communicated.

You notice that people who are aware of the study goals are more likely to report negative typical symptoms like irritability and pain than those who are unaware of the study goals.

You conclude that the reporting of the symptoms is influenced by demand characteristics. In other words, people who were informed about the study’s purpose thought that the researchers wanted to hear about the typical complaints related to the menstrual cycle. As a result they were more likely to report that they had experienced such negative symptoms.

Response bias can also distort the findings of a study.

The survey includes questions with binary responses such as:

| “Was the live virtual visit satisfactory?” | Yes/No |

| “Our live virtual visit feature is easy to use” | Agree/Disagree |

When the survey is closed, the admissions officer notices that responses are invariably positive. In this case, questions were worded in such a way that the respondents were more likely to respond positively to every question, choosing yes or agree, even if they didn’t necessarily agree with the statements.

How to minimize response bias

Although it may not always be possible to eliminate response bias entirely, there are a few steps you can take to minimize it:

- Keep your surveys short and to the point to avoid respondent fatigue.

- Use unambiguous language and avoid jargon when writing your survey questions and responses. In this way, your respondents will not lose interest or disengage due to the complexity of your survey.

- Use neutral language, particularly in surveys and interviews that probe into sensitive topics like politics, religion, or illegal substances.

- Make sure that your questions are interesting and relevant to your respondents.

- Use different question formats—e.g., scale, binary, or open-ended. Group questions by topic.

Withhold information that can place demand characteristics on participants or researchers when conducting experimental research. Setting up a double-blind study and using random assignment can prevent this type of bias from affecting your results.

Other types of research bias

Frequently asked questions

- What is the difference between response and nonresponse bias?

-

Response bias is a general term used to describe a number of different conditions or factors that cue respondents to provide inaccurate or false answers during surveys or interviews. These factors range from the interviewer’s perceived social position or appearance to the the phrasing of questions in surveys.

Nonresponse bias occurs when the people who complete a survey are different from those who did not, in ways that are relevant to the research topic. Nonresponse can happen because people are either not willing or not able to participate.

- What are different types of response bias?

-

Response bias is used to describe a number of different conditions that can lead study participants to answer falsely or inaccurately. Common types of response bias are:

- Acquiescence bias

- Demand characteristics

- Social desirability bias

- Courtesy bias

- Question-order bias

- Extreme responding

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

This Scribbr articleNikolopoulou, K. (2023, March 17). What Is Response Bias? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved November 3, 2023, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-bias/response-bias/

Aubuchon, P. G., & Calhoun, K. S. (1985, January). Menstrual Cycle Symptomatology: The Role of Social Expectancy and Experimental Demand Characteristics. Psychosomatic Medicine, 47(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-198501000-00004

What Are Demand Characteristics in Psychology Research? (2020, April 7). Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-demand-characteristic-2795098